What Grace Lies Underneath: Ocean Vuong, Satori, and Living as an Immigrant

Special Article for Asian American and Pacific Islander Heritage Month

When soft-spoken, gentle, and short-statured Ocean Vuong spoke about how he wanted to shoot someone for stealing his bike, it made me want to pause and listen.

My friend Kate sent the interview to me during one of the busiest and most exhausting weeks of my life. We were about to sell our house—closing was just days away—and there were a hundred things left to do. There seemed to be no time to do anything, much less listen to a podcast interview with a very successful Vietnamese writer and professor. Perhaps there was even a tinge of jealousy. Does he ever have to worry about cleaning a house for the next owners?

The last straw was when the electrician, after updating the house to satisfy the inspection report, told me a fan light still wasn’t working—even after replacing the bulb. He diagnosed the problem as a burned-out lighting element. I told him it was an easy fix I could handle myself, since the part needed to be ordered and installed. With only a few days until closing, I didn’t have time to waste. When the part arrived, I installed it with little effort, flipped the switch and... nothing. I took it apart and checked the wiring. I even used a 110V tester—it lit up. But I still couldn’t figure out why the LED bulb wouldn’t turn on.

Desperate, I dismantled the entire fan, thinking maybe a faulty wire was to blame. After a few exhausting hours, I picked up the remote and pressed the “light” button. The remote gave a weak signal. I wondered—was it just the battery? I drove to the orange big-box store, bought a replacement, popped it into the remote—and immediately, the light turned on.

On the way back to our new place, I stopped to fill up at a gas station. I turned on the Ocean Vuong interview from the New York Times. Even after the gas pump clicked off, I stayed there, sitting on the curb beside the car, listening. The smell of gasoline was in the air. The sun bounced off the concrete and warmed my tired body. In my ear I listened to a conversation that was heartbreaking and, at the same time, full of grace and poetry.

Ocean Vuong and his mother were refugees from Vietnam. His grandfather, described as a farm boy from Michigan, had served in the U.S. Navy during the Vietnam War. While stationed in Vietnam, he met Vuong’s grandmother and fathered three children. But when he returned to the U.S. for a visit, Saigon fell, and Vuong’s grandmother was trapped in Vietnam. Due to the collapse of South Vietnam, the children were placed in orphanages for their safety.

Vuong’s mother gave birth to him at 18. He was born as Vương Quốc Vinh and it was later changed to Ocean because his mother could not pronounce the word “beach” and it was suggested she used the word ocean. Because Vuong and his mother appeared to be of mixed heritage—likely the child of an American serviceman—they were at risk under the new North Vietnamese regime. To escape persecution, they fled to the Philippines and eventually sought asylum in the United States After settling in Hartford, Connecticut, Vuong’s father eventually left the family, never to return. Vuong was raised by his mother, grandmother, and aunt. Later, he reconnected with his grandfather, who had remarried a university professor. The contrast between families was stark—but the family that raised him, though illiterate, were storytellers. And those stories, he says, remain at the heart of who he is.

I won’t spoil the impact of Vuong’s story about working as a farmhand illegally, but what saved him was a moment of “satori”—an awakening—offered by the person he asked for a gun. The word satori (悟り) is a Japanese Zen Buddhist term meaning “awakening,” “comprehension,” or “understanding.” It comes from the verb satoru, meaning “to know.” His friend’s moment of insight—refusing to give him a gun—was an act of grace. He knew it would end badly if Vuong pursued revenge, and more importantly, it would have violated Vuong’s very essence.

During the interview, Vuong reflects:

I think what I'm trying to get at is that I didn't become an author just to...

like my goal was not to like have a photo in the back of a book and be like

an author. Writing became a medium for me to try to understand like what...

what goodness is.

Time and again, Vuong returns to this theme: writing as a medium for deep knowing—not the scientific kind, but the kind that touches mystery. That, he says, is what it means to be human. That is what he teaches his students: not only how to write, but how to know—themselves and the world—in this essential, luminous way.

Sitting there at the gas station, exhausted, relieved, frustrated—but aware—I thought about my own life and what I was doing. The problem wasn’t the light fixture. It was that I wouldn’t let someone else do the work, someone trained to do it. I burden myself unnecessarily, even when there are other options. These realizations are like pinpricks in a dark sky—my own small moments of satori—when I recognize how I create unnecessary suffering.

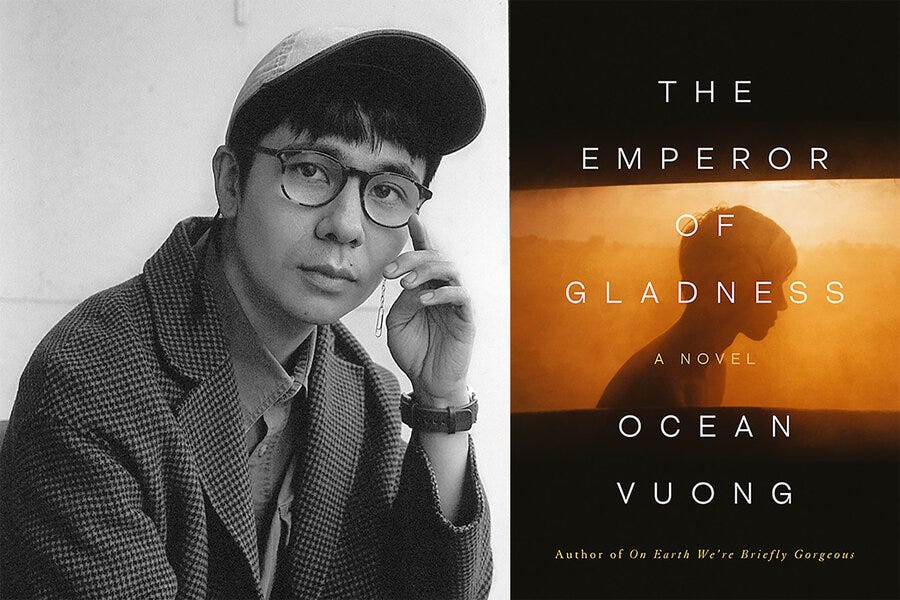

There are hardships we must endure, and there are moments when we can choose to escape. Vuong worked many menial jobs—Boston Market, tobacco fields—and one day, while working in the fields, he realized he had to get out. At a community college, he began reading Baldwin, Dillard, and Foucault. That was when he discovered that “writing was not writing a respectable email to get a job. It was a medium of understanding suffering.” Eventually, he earned an MFA in poetry at New York University. Later, he won the prestigious MacArthur Fellowship (the so-called “genius grant”) and is now a tenured professor in NYU’s creative writing department. His first novel, On Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous, is an extraordinary work blending memoir, philosophy, and queer love.

Several years ago, before the pandemic, I had the chance to meet Ocean Vuong at Brazos Bookstore in Houston. He was able to draw out many Vietnamese Americans from the community and it was encouraging to see a generation who valued the arts. What was special was that he called me anh, meaning “older brother,” and signed my book with a sketch of a boat, perhaps something he draws for everyone. However, we both knew what it meant: a vessel of discovery, an ark to safety, a way across a vast ocean.

Often, what we need is not to push harder into the unknown, but to pause—until a spark, a light, illuminates the way.

Have you ever reached a point in your life where you feel you're violating your own essence, yet feel powerless to change?

There is always a way forward.

We can build the boat together.

If you feel like someone could benefit from reading this, please feel free to share.

If you would like to continue to be a patron of articles like these, you can show your support here:

Listen to the full interview of Ocean Vuong here:

Or find it on The New York Times podcast channel wherever you listen.

Upcoming Book Tour:

Ocean Vuong will be on tour for his latest novel, The Emperor of Gladness. If you’re in Houston, get event details here:

Purchase the novel here

Hello there! Thanks for visiting our Andor podcast recently. I loved this reflection and wondered, are you based in Houston? I was born and raised there and went to Rice. Peace.